There lies a catch-22 in the heart of my design practice which I am not sure how to resolve. I have revered art and design since I was young, awestruck by the power and beauty that it can have. This is what led me to work in the creative field, thinking that graphic design is the ideal place where art and the ‘real-world’ intersect — a loaded statement, for sure. I embraced design joyously, striving to create work that is meaningful, and not merely focused on aesthetic values. I wanted to create a practice that would transcend my life and speak of deeper, spiritual truths.

By Cristóbal Ayala

However, as I’ve grown older, a disquieting reality has slowly revealed itself. Graphic design, unlike art, serves a purpose, and in the commercial world it appears to have the sole aim: to sell. It has to maintain the mechanism that brought it into existence in the first place, which is a deeply flawed capitalistic system. There is nothing objectionable with the exchange of goods, but I am hesitant to participate in a consumerist and materialist system that is pushing our planet and society to the breaking point. How can I cultivate a design practice that allows for personal spiritual growth, if it is held up by an inherently immoral system? Therein lies my quandary.

As my education in design progresses, there is a dormant question which unsettles me. The glossy sheen, the neat, colourful aesthetics which dominate the field today, all with an obvious commercial function — what is it for? There has to be more to design than being a tool for capitalism. In fact, I’m sure of it — I just need to be able to identify it for myself. I do not want to be a cog in the consumerist machine that always promises something better, all the while leaving us more empty and dissatisfied than before. As Stuart Walker recently wrote in his book, consumerism ‘may be attractive, easy and ceaselessly captivating, but [it] also promotes temporal pleasures that, ultimately, are unfulfilling.’ As communicators, we are ultimately the ones who sell the lie of consumerism to the public. The irony is that consumerism and materialism are not only detrimental to our individual search for peace and happiness, but absolutely antithetical to it.

“There has to be more to design than being a tool for capitalism.”

I do not wish to contribute to the ‘Society of Spectacle’ that Guy Debord described so accurately in the 1960’s, reducing reality to an ‘endless supply of commodifiable fragments, while encouraging us to focus on appearances.’ It is a hard truth to face, but for the past few decades design has mainly been used to promote and maintain a version of lived reality which is driven by economic interest and profit. There is infinitely more to life than the next thing we can consume, but as Debord says, it seems that in our modern world ‘there is no clear objective, no end to all this busyness, and no higher sense of purpose than the wish to produce more stuff more quickly. And in the process we eliminate stillness and sacrifice peace.’

FORGING A DIFFERENT PATH

Looking at practitioners that have dealt with these topics, I have found there is a way forward, but I will have to forge my own unique path. Someone who I deeply admire is famed activist and artist Corita Kent, not only for her work but for the way she understood that anything can be sacred; anything can be a stepping stone on the path to transcendence. Writer Theo Inglis once described her process as taking ‘the signage of everyday life and using it to express her own form of liberal spirituality.’ Through her art, Corita demonstrates how the act of creation can be profoundly meaningful, not solely on an individual level but for society as well.

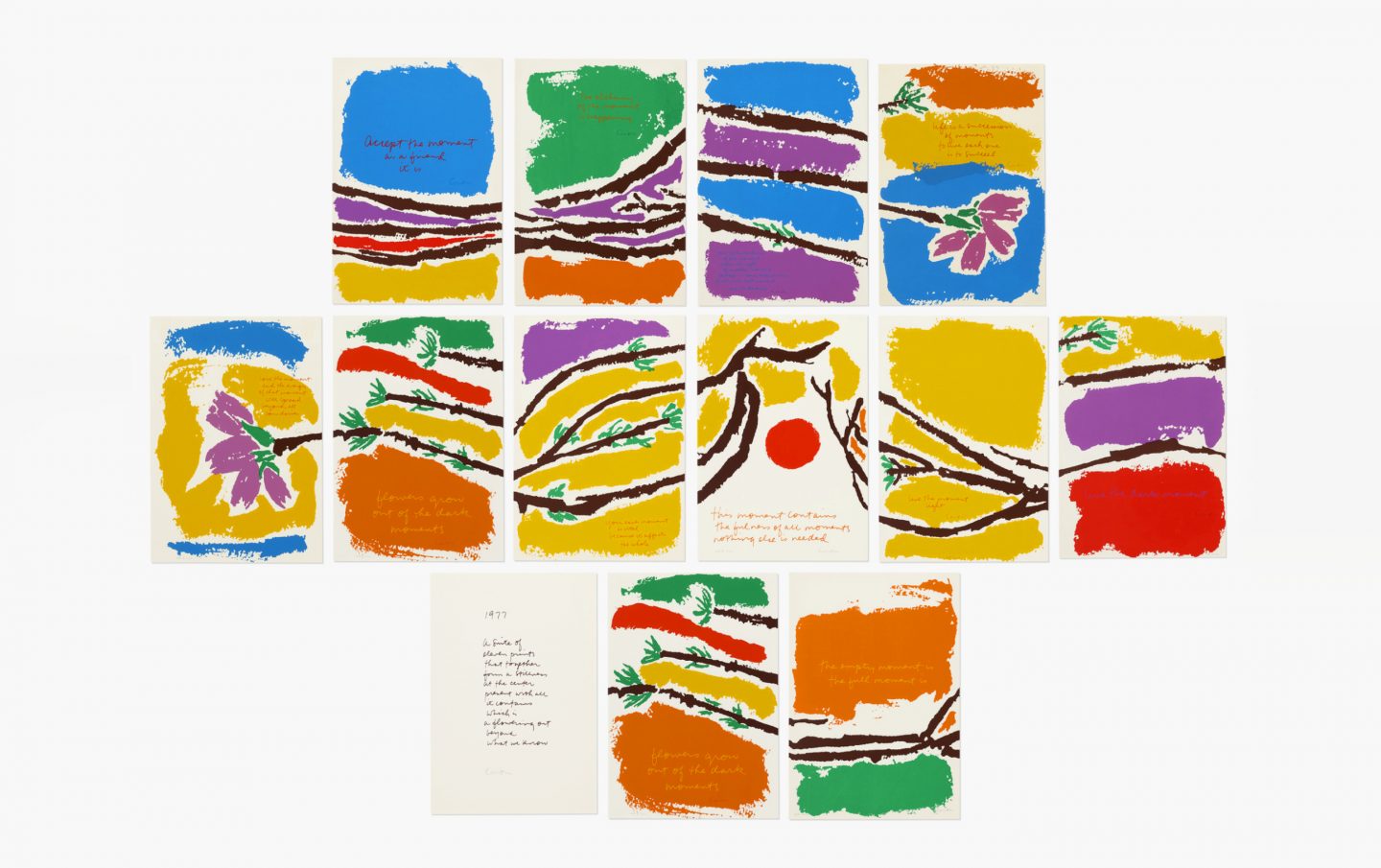

Details from Moments (1977) by Corita Kent. Copyright of Corita Art Centre.

One of my favourite collections of hers is Moments (1977), an array of meditative, abstract and nature-oriented screen-prints she made while grappling with her cancer diagnosis, solitude and living through tumultuous times. Out of the Darkness communicates beautifully her inner struggle and eventual acceptance of her situation: “Out of the darkness / of one moment / grows the light / of another moment / perhaps in some distant time / if not in the next moment / love the darkness.” I cannot begin to fathom how many individuals, religious or otherwise, have found solace and healing through her poetry and designs. Corita broke free from the limitations of what it means to be a designer, artist, or even a nun, creating something radical and meaningful in the process. This is what I aspire to; seamlessly merging my practice as a designer with my moral and spiritual values.

A WELL-DESIGNED LIFE

In short, my design practice and life can be distilled into this question: What does it mean to transcend? To transcend is to break free from our own self-imposed limitations, to self-actualise to our greatest potential. What we can all individually aspire to is a deeply personal topic, and I do not presume to answer that question for anyone else. Personally, I have my sights set on the highest goal – and that is spiritual by nature. I wish to live an examined life, as Socrates famously stated, and that means being able to relate to my work in a way which I find meaningful. A life examined is a life well-designed, as design is the tool that allows us to structure and relate to our world. And a well-designed life allows us space and room to breathe, to be present with ourselves and our communities, not merely focused on what we can obtain from the world but rather what we can give to it. I am not sure how to achieve this vision, but here are some working principles which I wish to adhere to:

1) Learn. I should always be learning, either new techniques, philosophies, or whatever feeds my soul and mind.

2) Play. I should always be playful, and constantly be taking risks. As Paula Scher states, I should never let anything become solemn or mechanical. Design should be genuine, never contrived or forced.

3) Contextualise. I should remain connected to my personal history and culture while allowing space for new communities and relationships to form. I should draw from my wellspring of experiences and intuition, allowing my actions and designs to become personally significant.

4) Inquire. Finally, and most importantly, always be asking why. Why am I doing this? How will this action, project or brief be significant or helpful towards society at large?

I do not pretend to know what it is exactly that I want to achieve, or how I will achieve it. However, I do believe that ‘a wise society, by necessity, is a post-consumer society.’ I cannot stand idly by watching my world destroy itself over the course of my life. My work, my art, my journey to live meaningfully is a long and winding road, and the sands beneath my feet will always be shifting. However, I know that design can change the world for the better, and that it is a transcendent and powerful tool that I will not waste. It remains up to me to see in which way I wield it.

Top image: Spheres of Knowledge by Cristóbal Ayala.

About the author

Cristóbal Ayala is a Mexican designer living in London. He is currently a first year student at Central Saint Martins studying Graphic Communication Design. To see more of his work, visit his website and Sin Tesis Studio.

SUBMIT A STORY

Would you like to see your writing featured on the What Design Can Do blog? Learn more about our written submission platform here.