At the core of our climate emergency is a planet that’s growing hotter and hotter by the season. Rising temperatures on Earth are thawing ice caps, causing extreme weather disasters — even increasing the risk of pandemics. The Paris Climate Agreement shows that at least 192 countries are aware of this, and of the urgent need to contain global warming to below 2 degrees Celsius. But just five years on, our wasteful economies have already pushed us over the 1 degree threshold. Besides fossil fuels, what is driving this runaway train? How would tackling waste help reduce CO2 emissions?

Earlier this year, What Design Can Do launched the No Waste Challenge in partnership with the IKEA Foundation: a global competition calling for imaginative ideas to reduce waste. As part of our deep dive into the subject, today we’re breaking down the crucial links between waste and climate change — and finding out exactly why some call it “the mother of all environmental problems.”

THE GREAT ACCELERATOR

So, how DOES waste contribute to global warming?

Here’s the reason why we call waste a wicked problem: first, it is global, systemic, and increasingly difficult to solve. Second, as the endpoint of our linear economy, it also has a disastrous impact on all other social and environmental problems. In our quest to make, sell and consume more and more stuff, we produce enormous amounts of greenhouse gases such as carbon, methane and nitrous oxide, which cause global warming. In fact, the extraction and processing of natural resources currently account for a full half of total greenhouse gas emissions worldwide!

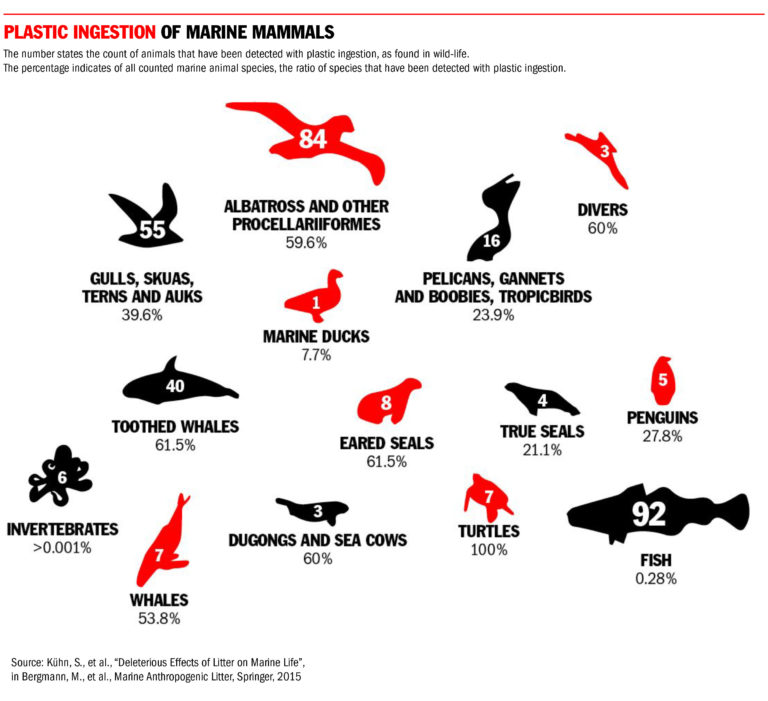

Meanwhile, our existing waste infrastructures are often chaotic, exploitative and ineffective. According to the World Bank, waste rotting in landfills and burned in open fires are releasing pollutants into the air, contributing to nearly 5 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Uncontrolled dumping — especially of toxic and hazardous waste — also threaten our wildlife populations. This is most visible in our oceans, where 100,000 marine mammals die every year as a result of plastic pollution, and at least two-thirds of the world’s fish stocks are suffering from plastic ingestion.

This loss in biodiversity is extremely harmful to our climate, because it accelerates the collapse of healthy ecosystems. If things continue the way they are, up to 50% of all plant and animal species will be exposed to dangerous climate conditions by 2100. The effect of this would be extensive, because rich, biodiverse environments actually mitigate against climate change, and remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. If we lose them, we lose what makes our planet resilient — and our best hope at adapting to a changing climate.

Which industries are the biggest culprits?

While most greenhouse gas emissions are caused by the burning of fossil fuels, food production takes the cake for being one of the most wasteful industries on the planet. Currently, our food system is responsible for about one quarter of our total annual greenhouse gas emissions. Much of the harm occurs in the way we raise and harvest all the plants, animals and animal products we eat. Everytime we clear a forest for cattle, soy, palm oil, or coffee production for example, we destroy habitats and release large stores of carbon into the atmosphere. Livestock also produces huge amounts of methane.

After all this, almost one third of all the food we produce still ends up lost or thrown away. This adds yet another layer to the problem, as organic waste also releases methane as it decomposes. To make a long story short: if we want to keep global warming under control, we’ll have to learn to feed more people with less resources, particularly as the world’s population keeps growing.

Of course, we also have to mention plastic production here, as the material remains one of the most persistent pollutants on Earth. It is also one of the most popular — we consume so much of it that recyclers can’t keep up. To give you an idea: worldwide we are using nearly two million single-use plastic bags a minute. By 2050, when plastic production is expected to have tripled (!), it will be responsible for up to 13% of our planet’s total carbon budget. And besides killing wildlife, plastic waste in our oceans also releases methane and ethylene as it breaks down, creating an alarming feedback loop that makes temperatures rise faster and faster.

Didn’t COVID-19 buy us some time?

To a small extent, yes. Thanks to our reduced activity, carbon emissions have fallen by some 7% in 2020, the largest absolute drop in emissions ever recorded. Unfortunately, experts say that even a decline like this will do nothing to slow the pace of global warming in the long run.

This is because we’re dealing with a legacy of hundreds of years of ‘take-make-waste’. Before the lockdowns of 2020, the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere was the highest it had been in over 800,000 years. We’re going to need a lot more than a year of working from home to make a dent in that. We also have to reckon with the fact that the pandemic actually created a new rush for single-use plastics.

“We have an opportunity to reinvent everything. This is the moment, not just to tweak at things, but to think laterally about how our world should be redesigned.” — Alice Rawsthorn, author of Design as an Attitude (2018)

What can designers do about it?

With so much stacked against us, climate change may feel like too big a problem to solve. That’s precisely why we can’t leave it to politicians or scientists to solve alone. If we look at the action plans that have been drafted in recent years, most focus on ending our reliance on fossil fuels, and paving the way for clean energy technologies. This makes sense, because if we do this well, we could address 55% of today’s global greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

But to tackle the remaining 45%, we need to consider the taking and the making of all of the things we use and eat. This is where the circular economy comes in. In fact, applying circular strategies for just five of the most common materials in our economy — cement, aluminium, steel, plastics, and food — can eliminate 9.3 billion tonnes of CO2 by 2050. All of this can be done, and designers and creative entrepreneurs are in a unique position to make these changes a reality. In many ways, design sits prominently at the heart of the circular economy and thus in the transition to a more sustainable future.

PUT INTO PRACTICE

So how can we design in a way that protects all life on the planet? If you’re a creative or innovator working on solutions for the No Waste Challenge, or simply looking to reduce the impact of your work on climate change, here are a few helpful tools and resources that you can take into consideration.

LEARN FROM MOTHER NATURE

“Life has been on the planet for 3.8 billion years, and in all that time, it has learned what works and what doesn’t. That’s a long line of good ideas,” said author and biologist Janine Benyus, who is a pioneer in the field of biomimicry. When she coined the term in 1997, it was an emerging discipline that had just started to grab the attention of creatives around the world. Now, it has become a powerful movement, spawning a slew of other visionary ideas and research — from Neri Oxman’s work in material ecology, to Koert van Mensvoort’s concept of Next Nature.

In all its manifestations, the basic attitude remains that the most effective and elegant design solutions are those that can already be found in nature. It runs on the belief that the future of design is not just about shaping our environment, but about letting our environment shape us. From resilient forms of architecture to ingenious ways of dealing with waste, there’s a lot we can learn from a 3.8 billion-year-old designer.

“In order to design our way out of the environmental crisis we ourselves have created, we must first learn to speak nature’s language.” — Neri Oxman, designer

Don’t forget energy

As we mentioned earlier, circular design is only half of the story. To make sure that a product, system or service is truly climate-friendly, consider how it uses energy. Does it run on fossil fuels, or can it be redesigned to work with renewable sources? How much energy does it require to produce? How much does it waste? Could it be embedded in a better, more circular system — like Marjan van Aubel’s solar roof? Or could it create one — like Carvey Maigue’s Aureus project, a solar film made out of crop waste?

Marjan van Aubel’s solar roof as part of the Dutch Pavilion at the upcoming World Expo. Renders ©V8 Architects.

Carvey Maigue’s Aureus solar material.

USE optimism

Finally — despite everything — we suggest being radically, actively optimistic. Not to ignore the extraordinary turbulence of the last year, or the massive challenge ahead of us, but to find surprising, agile ways to turn these things into something useful, or even beautiful. Design is all about possibilities, and as Michelle Ogundehin wrote in her 2021 forecast, in the face of crisis we must be bolder and braver than ever. It’s the only way for us to prove that we can be “as brilliantly inventive as we have previously been so terribly destructive.”

“Creatives can make arguments sharp, ideas desirable, protests compelling and movements irresistible. All of that can and must happen.” — Naresh Ramchandani, cofounder of Do the Green Thing

Are you low on inspiration? Read up on tips to deal with eco-anxiety, or watch this interview with industry icon Bruce Mau, on what it means to design ‘for good’ when times are very, very bad. Prefer a live conversation? Follow the brilliant Design Emergency series on Instagram for weekly check-ins with some of the most exciting creatives who are changing lives today. Or, join the promising New World programme by It’s Nice That, a 12-week series of free virtual sessions exploring “the power of creativity to build back a better world.” Finally, for earth-centred discussions of the print variety, we suggest a peek at refreshing, forward-thinking indie titles such as Emergence Magazine and It’s Freezing in LA.

Of course, you can also bring your ideas, concerns and conversations to the #NoWasteChallenge, by entering a project or by adding your voice to our community of change-makers. We’ll be waiting!

Presented by the No Waste Challenge, this article is the third in a three-part series exploring the true cost of consumerism, and the enormous impact of waste on climate change. Read the previous article here: ‘Why waste is a socio-political issue’.