As a young black woman growing up in Leicester, I saw early on the harm that branding, advertising and mainstream media can place on marginalised groups. I also became acutely aware of the role it played in marginalising them to begin with. Intuitively, I understood symbolic violence—covert oppression via cultural symbols and norms—without knowing that the term existed. Because like most people who belong to marginalised groups, I had felt this violence firsthand.

By Najite Phoenix

But after a while, it occurred to me that by itself, my lived experience was not enough to understand its complex history in depth. So I decided to pursue a master’s degree in Brands, Communications and Culture, as a way to properly challenge and explore my intuitive hunches.

During the first semester of my studies, I was introduced to the colonial history of branding and how the advent of modern advertising in the West went hand-in-hand with colonialism. I learned that essentially, as colonial religious doctrine began to lose its influence, and scientific racism remained accessible only to a small, highly-educated portion of society, brand advertising became the coloniser’s next most effective tool to justify colonialism and promote the supposed superiority of the Western world.

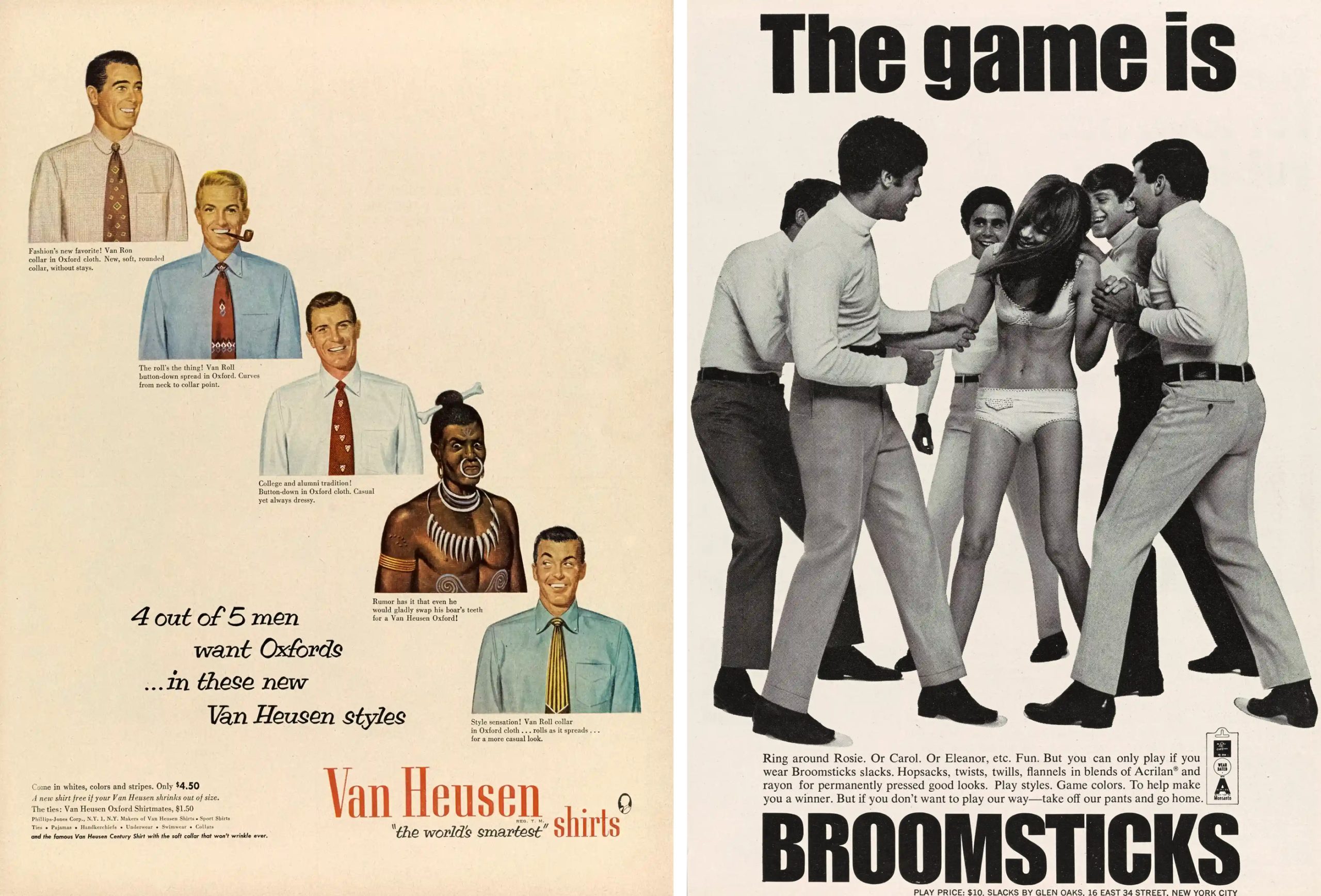

Turning primarily to household goods such as soap and detergent, they found that these were the perfect products to spread harmful black vs white, east vs west and male vs female narratives, based on these binary oppositions. The narrative spun was this: Black and brown people were inferior, dirty savages who needed civilising by their white, clean, superior counterparts. Essentially, this story was used to assign people to their social categories; teaching people how each group should behave and be treated.

Left: An advertisement for Elliott’s Paint, 1930s. Photograph: Lake County Museum/Corbis. Right: An advertisement for Pear’s soap, 1880s. Photograph: Wellcome Collection gallery (2018-03-23).

You see, advertising has always been about more than just selling products; it’s also about selling ideas. This is what made it a powerful tool for colonialism and, just as importantly, a potential force for decolonisation. While some may question the feasibility of using the ‘master’s tools to dismantle the master’s house’, I want to make one thing clear: branding and advertising are not the master’s tools. Yes, they were strategically used by the West to meet its aims. But it wouldn’t be the first time the West had borrowed from the East in order to get ahead.

The symbolic art of branding, and the storytelling dimensions of marketing, has indigenous, eastern roots. Words like storytelling, myth, archetypes and ritual are commonplace in modern advertising. And there are more similarities than differences between a talisman—an object believed to possess metaphysical powers—and a branded watch that sells for thousands of pounds, because it promises the owner status, power and transformation. Yet when words like decoloniality and indigenous are used in the context of branding, it’s usually through the lens of ‘adding’ indigenous knowledge to this field, with little acknowledgement of the fact that this is exactly what the industry is built on.

‘The symbolic art of branding, and the storytelling dimensions of marketing, has indigenous, eastern roots.’

Serendipitously, at the time I was studying my masters, I was also formally studying West African indigenous spirituality, periodically travelling to Togo and Burkina Faso to study with Elders in the bush, in the weeks leading up to my first semester assignments. When I returned, what I experienced was quite remarkable. Each lecture seemed to mirror what I was learning within the context of African indigenous spirituality. For example I’d attend a university lecture on the use of rituals in mainstream society and then attend a class on the same subject but from an indigenous perspective. Or I’d learn about rites of passage in indigenous cultures and then attend a university lecture on how these rites of passage show up in mainstream institutions such as university and government. The two had so much in common that each strengthened my understanding of the other.

During this period, I began to envision the future of branding from a decolonial perspective. I saw it not as the repurposing of a Western tool but as the reclamation of a tool inherently rooted in indigenous traditions. As I delved into the study of traditional healing, I discovered that, broadly speaking, the indigenous view of healing centres around restoring balance—whether it’s balance in the mind, body, spirit, or society.

From this perspective, decolonial branding and activism can be seen as forms of healing, focused on crafting communications that address the harms inflicted by the symbolic violence of colonialism and imperialism. It struck me that, similar to how a healer assesses an individual’s physical state for imbalances and addresses them, those working in branding, marketing, and advertising may serve as healers for society. In this way, our role is to assess the state of the industry for imbalanced narratives and reintroduce balance into its ecosystem.

The fact that the coloniser chose branding as a means to perpetuate their agenda in place of the dwindling power of religious and scientific racism, underscores the inherent potency of branding. This power hasn’t waned over time; rather, it has grown stronger. It has also become increasingly democratised, allowing more people to participate as producers—not just consumers—contributing to the (re)shaping of our cultural landscape. This is just one of the reasons I advocate for using brand communications as a decolonial tool.

Left: An advertisement for Van Heusen shirts, 1952. Photograph: Life. Right: An advertisement for Broomsticks, 1967. Photograph: GQ.

But what does this look like? The indigenous worldview of communication is that it should ultimately ‘further’ or ‘enhance’ existence for the better. Decolonial, anti-oppressive and restorative communications isn’t just about randomly scattering people from marginalised groups into brand/advertising visuals or messaging in a favourable light. It’s about understanding that our society is sick. We have built a culture that privileges certain principles over others: light over dark, masculine over feminine, Yang over Yin. It paints the doer as superior to the thinker; man as superior to nature; fast as superior to slow and so on and so forth.

‘Decolonial branding and activism can be seen as forms of healing, focused on crafting communications that address the harms inflicted by the symbolic violence of colonialism and imperialism.’

The coloniser viewed every opportunity to brand and market products as opportunities to push these kinds of harmful messages. As a result, our ecosystem is in a dire state. Our role then, is to intentionally use each brand and marketing opportunity to disseminate messages that heal. Messages that re-dignify historically marginalised identities and ideas, leading to a restoration of societal balance.

What we do and create is important. But how we present and talk about what we do and create is just as sacred. It’s also a way to connect with our ancestral thread and reimagine important, age-old roles, in the now. You might begin, for example, by figuring out which type of practitioner you are. Are you a Ritual Keeper (Experience Designer); Scribe (Copywriter) or Cultural Advisor (Consultant)?

Returning these concepts to our understanding of branding and design is an important part of decolonial practice. As are asking questions like: When designing experiences (rituals), how might you use these to facilitate community healing? What are the limitations of harnessing the power of branding for healing under a capitalist economic system that, by nature, undermines many indigenous values? How might you encapsulate the dignity, purpose and identity of people, places, projects and products as a strategist or designer? As an advisor, how might you ensure that this work remains purposeful and sacred?

For me personally, the experimental exploration of this questioning is slowly becoming ‘the work’. It’s a means for me to revisit the ancestral wisdom and practices I was torn from; and to begin to re-thread them and make use of them, in the now.

About the author

Najite Phoenix is a decolonial communications strategist, semiotician, poet, and polymath, with an MA in Brands, Communications and Culture. She is the founder of Decolonial by Design, a digital learning platform and consultancy that supports organizations to decolonize the way that they approach, think and talk about their work. More broadly, her work centers on fostering a sociological imagination, helping individuals to shed false dichotomies and supremacy narratives, while approaching their work with a deeper sense of meaning and purpose.

SUBMIT A STORY

Would you like to see your writing featured on the What Design Can Do blog? Learn more about our written submission platform here.