There is a growing consensus among climate activists that we need to move beyond the linear economy — and fast. The pandemic has made it clear: if what we’re looking for is a healthy future for both people and planet, we won’t find it in ‘business as usual’. But where do we go from here? What exactly are the old models we ought to leave behind? How much damage have we already done? And why should designers care?

Earlier this month, What Design Can Do launched the No Waste Challenge in partnership with the IKEA Foundation: a global competition calling for radical ideas to reduce waste and rethink our entire production and consumption cycle. As part of our deep dive into the subject, today we’re answering a few key questions about the creative industry’s role in the ‘take-make-waste’ economy. If you’ve ever wondered how design got us into this mess — and how it can help us transition out of it — keep reading.

Out with the old, in with the new

So, what exactly is the ‘take-make-waste’ economy?

When we talk about ‘take-make-waste’, what we’re talking about is an approach to resources. This model is the basis of the linear economy, in which raw materials are collected, transformed into products which are used briefly, and then thrown away. Take, make, waste.

In this system, value is created by producing and selling as many products as possible. The problem is, it operates on the assumption that there will be an infinite supply of raw materials, energy and labour. Today, we are seeing just how wrong that assumption was.

“Today we have economies that need to grow, whether or not they make us thrive. What we need are economies that make us thrive, whether or not they grow.” — Kate Raworth, author of Doughnut Economics (2017)

Why is it so unsustainable?

In a linear economy, waste is the end point; the full stop. Because of this, all kinds of waste are now threatening our ecosystems: plastic waste, textile waste, food waste, electronic waste, construction waste; just to name a few. The numbers are staggering: our landfills are growing by some 2 billion tonnes of garbage every year. If all this waste was put on trucks, they would stretch around the Earth 24 times. Meanwhile, one-third of all the food produced for human consumption is wasted, and a whopping 8 million tonnes of plastic end up in our oceans every year. Many of us know this, yet still we continue buying more and more stuff.

Before it even reaches the consumer, this economic chain also produces enormous amounts of greenhouse gases such as carbon, methane and nitrous oxide. In fact, the extraction and processing of raw materials currently account for a full half of total global greenhouse gas emissions. Water and land are also exploited throughout this process, leading to alarming rates of habitat and biodiversity loss. All in all, according to the Global Footprint Network, we are already consuming 75% more resources than the earth can sustain in the long term.

How has bad design contributed to the problem?

Everything around us has been designed: the clothes we wear, the buildings we live and work in, even the systems that deliver our food and mobility. Unfortunately, since the industrial revolution most things have been designed to fit the linear model, where life cycles are short and materials are nearly impossible to recover.

We are all a part of this system. As Cradle to Cradle author William McDonough reminds us: waste and pollution are not accidents, but the products of what he calls crude and unintelligent decisions. By making things by turns desirable and disposable, the design industry has actively encouraged consumerism, contributing to over-extraction, over-production and over-consumption. Our fingers are in almost every pie: from the advertisements we see, to the algorithms we don’t, and the millions of products, trends and brands in between.

“Up to 80 per cent of a product’s environmental impact is baked in at the design stage.” — Katie Treggiden, author of Wasted (2020)

But here’s the good news: we can do better. Designers are in a unique position to change how things are made and what they are made of. Design also has a role to play in shifting narratives and facilitating alternative visions of the future. And there is reason to be optimistic — many designers and creatives have already taken an active role in the transition to a new system that works for both people and planet.

What is a circular economy?

The circular economy is an alternative framework for designing, making and using things within our planetary boundaries. Unlike the linear economy, it is restorative and regenerative by design, and prevents waste by recovering and reusing as many products and materials as possible.

It is based on three key principles:

- Designing out waste and pollution

- Keeping products and materials in use

- Regenerating natural systems.

In other words, the circular economy tries to embed things in cycles: take, make, use, consume, regenerate, restore, reuse. But it is more than just recycling; it is a dynamic and complex system that requires radical change in almost every sector. It demands that we reframe our ideas about waste (to view it as a resource); growth (to decouple it from consumption); and nature (to understand that we must fit our economy to nature, not nature to our economy).

Does it really work?

Research suggests that yes — a circular system would have a positive impact on both the planet and the economy. If we made the transition today, we would halve the amount of CO2 emissions in our atmosphere by 2030. The consumer goods industry would save some USD 700 million in annual material costs, and a significant amount of new jobs will be created in innovative design and business models, research, recycling, and product development. Circular strategies can also provide a resilient economic recovery from the COVID-19 crisis: one that is inclusive and prosperous in the long-term.

At the same time, the circular economy is not a panacea. For the transition to be truly sustainable, it needs to be bolstered by progress in other sectors, for example in renewable energy. In this, there’s still a lot we have to learn. What it does provide, are plenty of exciting opportunities for innovation, and a valuable new set of goalposts.

“Designers today have an amazing opportunity to be part of building a restorative, regenerative future. A future where we can recover materials and feed them back into the economy.” — Ellen MacArthur

PUT INTO PRACTICE

So what can creatives do to help move beyond the take-make-waste economy? Here are a few helpful tools and resources that you can take into consideration.

Learn the circular design process

There is already a wealth of information out there that can help you to create more elegant and effective solutions for the circular economy. We suggest checking out the Circular Design Guide by IDEO, or this toolkit by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. They’ll help you ask the right questions, like: What happens to your product at the end of its use period? Can it have many use periods? Is it made from recyclable and recycled materials? Is it open-source, easy to repair, or designed for disassembly? Can it deliver even more value in the future?

“Instead of making new products, design can be used as a tool to repair what is broken; like our relationship with nature, and our relationship with things.” — Simone Farresin, Studio FormaFantasma

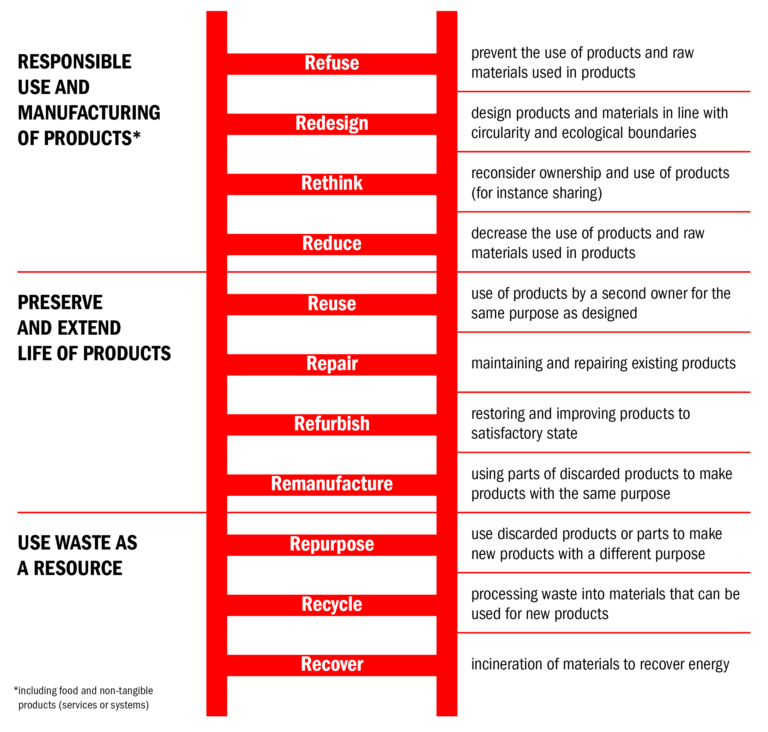

Consider the R-ladder

The ‘R-ladder’ is a diagram that can be used to rank and prioritize strategies towards a circular economy. Generally, strategies higher up on the ladder (such as those for rethink, reuse and repair) require fewer resources, and therefore have more impact in the long-run. At the bottom of the ladder, are strategies for recycling and recovery, which are helpful, but should still be limited because they often destroy some value or lower the quality of resources. This concept offers a valuable checklist for innovators. It helps you to remember the true goal of any circular system: which is not just to handle waste more responsibly, but to use less resources, and make fewer products. If your idea doesn’t serve that ultimate purpose, it might be time to go back to the drawing board.

Be generative

Finally, it pays to remember that a perfectly closed loop is a goal, and not a standard. Economist Kate Raworth suggests that instead of aiming for ‘mission zero’, we should work towards a generative goal that creates so much value that it gives back to everyone, just like nature does.

Admittedly, to do this at a significant enough scale, we have to redesign almost everything. But the transformation is already underway, and the potential is enormous. “At the end of the day, there is no good or bad design. It is how people and organizations employ design,” reflects Richard van der Laken, creative director of What Design Can Do. “What I want to say is: design is always a tool, a language. It is never an end goal. So, the real question is, do you want to use it in a good or in a bad way?”

Presented by the No Waste Challenge, this article is the first in a three-part series exploring the true cost of consumerism, and the enormous impact of waste on climate change.